Head In The Clouds

The largest design conceit in RTS games is the most obvious one – the viewpoint. RTS games have always used a top-down perspective of one kind or another, from Stonkers and Dune II right through Dungeon Keeper and Theme Hospital into the present day.Modern games tend to give the player more control over the scene, true, but even though you can zoom all the way in in Tiberium Wars doesn't mean that you do – nearly all gamers will acknowledge that in an RTS game you generally want to see as much of the battlefield as possible. World in Conflict and Supreme Commander even went the extra step of providing multi-monitor support so that full tactical maps could be displayed on the extra screens.

Although Magnus had already told me that designers basically have to ignore these gaming conceits in order to create a game which is fun to play, I still wanted to know more. I wanted to know how the viewpoint specifically might affect the story. Was the story dictating the presentation or the other way around?

"Most of the genres we're seeing in the charts today precede the advent of real storytelling, it's usually the case that the story has to adapt to the presentation and not the other way around," Magnus admitted. "In RTS games, for instance, you're flying around high up in the clouds with a bird’s perspective. It would not make a lot of sense to have person-to-person drama played out on the ground (with facial animations, etc.) without taking control of the camera and forcing the player to watch."

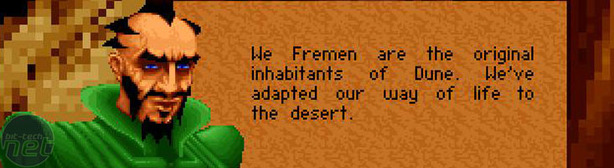

Early RTS games didn't have such simple designs - in Dune I players had to recruit troops in person!

"Compare that to FPS games such as Half-Life, where you can lock the player into a relatively confined space and have people-to-people drama play out right there in the room with you. Under such circumstances the designer doesn't have to take control of the players camera since there is practically zero likelihood of players missing the fact that there is something happening unless they do it deliberately."

Again, finding the balance between story and fun seemed to be the most important thing to Magnus. The birds-eye viewpoint may not be truly representative of the reality, nor does anybody really try to explain it story-wise – but it makes the game accessible to RTS newcomers and familiar to RTS veterans. It puts the whole experience in an understandable context and gives a safe, established point from which the rest of the game can be exposited.

The standard RTS viewpoint is also fitting given the sheer scope of most RTS games. Often in a strategy game you'll be using your ability to multitask – building a camp, fighting two or three skirmishes at once and trying to monitor your defences too. It doesn't matter whether you're laying scorched earth in World in Conflict, directing a giant robot in Supreme Commander or torturing your Dark Mistress in Dungeon Keeper – all strategy games tend to have an epic scope.

It turned out that even the scope and setting of the war in World In Conflict was subject to the vs. gameplay tradeoff.

"Yeah, you need a big friggin' war for starters. And those aren't easy to come by if you want to use a present-day setting, hence all the historical and sci-fi games. In fact, us going with the Cold War for World in Conflict was dictated by the fact that this was the closest period in time we could find when there could have been fighting on the scale needed while retaining some shred of plausibility," Magnus told me.

"But you must never lose sight of the fact that it's an action game and not a simulator. That's why we had the Soviet invade the US knowing full well that it wasn't very plausible at all. The fun of blowing up suburbia basically outranked the concern for how realistic a US mainland invasion really was."

"You can over-do it though. The key missions in the single-player campaign are of course important to the outcome of the war but it's nice to have missions that high command doesn't care that much about. If every mission was so important then it would de-sensitise the player, so we chose to focus on the character's internal conflicts and actual battles instead of the outcome of a global conflict"

"Make a setting that serves your gameplay, and then you make as good a story you possibly can while still enhancing gameplay. In some games the story pretty much is the gameplay, which further complicates things. But that’s basically how most RTS games work at least," Magnus summed up.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.